The Paper Trail (Europe and the Printing Press)

- Adriana

- Oct 6, 2018

- 2 min read

It's been a while since my last post on the book The Paper Trail by Alexander Monro. As my days passed by constantly pressing (and I mean pressing on presses, on kid's schedules, on migraines, on doctor's appointments, and on all other pressing matters), I forgot to continue reading and enjoying this amazing book. But today the book found me and, if only for some minutes (migraine didn't allow for much concentration and light), I was able to learn some more about the importance paper had and has in our life.

European paper-making began in Muslin-ruled Spain in 1056, by the town of Xativa (San Felipe). They used metal gauzes to make paper, which left more pronounced "laid" and "lines" on the paper.

In 1276, the first significant Italian paper mills were set up in Fabriano (I'm guessing some of you already know this name). Many of the Fabriano mills were simply converted from older grain mills. The Italian paper makers dislodged the Arab competition aided by better mills and more abundant water supply. The ingredients were cheaper too, as they used hemp and flax as raw material for paper.

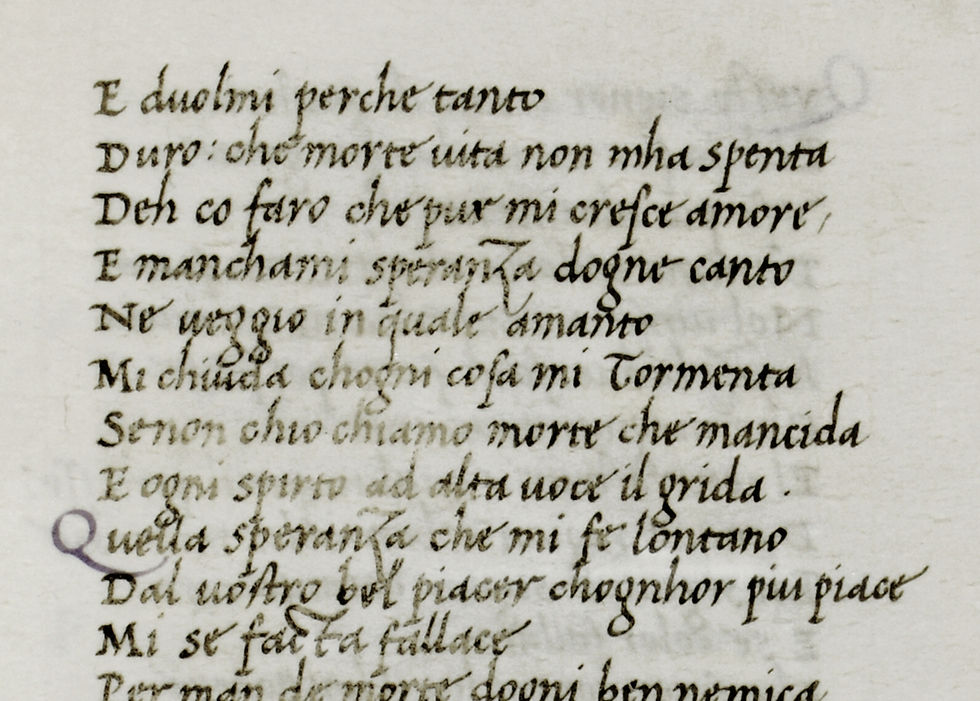

By the end of the 14th Century, the switch to cursive handwriting had increased the speed at which the scribes wrote. As paper and cursive script brought the price of books down, they began to get into the market less familiar with Latin, and so texts in local languages became more common.

In 1444, Cosimo de Medici established Florence's first public library. He believed that the study of Plato could purify Europe's Christianity of its moral depravity. When the Turks conquered Constantinople, more scholars of ancient Greece fled to Italy, specially to northern cities like Florence. In the 1450's, the status of the "writing master" grew rapidly. New handwriting developed, replacing the "Gothic" (first picture) with a quickly written, clear and angled script they called "Humanistic Cursive," where many of the letters were joined up. It was later renamed "Chancery Cursive," then "Italian hand," and finally "Italic" (last picture).

Despite these advances, it was handwriting (not paper making) which remained the slowest element of the process. Thus the greatest development for paper came from a goldsmith and publisher in Germany (do you know who he was?). IT CAME IN THE FORM OF A PRESS!

I'm going to stop here, because the next chapter is too exciting to put it together with this one. Thank you all for taking the time to read a little bit of history and I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did (which I very much doubt).

Comments